Ardabil Carpet

| Ardabil Carpet | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Name | Ardabil Carpet |

| Original name | فرش اردبیل |

| Alternative name(s) | Shaykh Safi Carpet |

| Origin | Iran |

| Date | 1539-1540 |

| Period | Safavid |

| Artist/Maker | Maqsud Kashani |

| Name Museum | Victoria and Albert Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

| Acquire Date | March 1893 |

| Gallery location | Islamic Middle East, Room 42, The Jameel Gallery, case 21 |

| Technical information | |

| Common designs | Medallion with 16 satellite ovals, Lamps |

| Common motifs & patterns | Blossom, Rosettes, Floral Meander |

| Dimensions | 529.5×1032.5 |

| Common colors | Dark Red, Red, Light Red, Yellow, Green, Dark Blue, Blue, Light Blue, Black, White |

| Dyeing method | Natural |

| Foundation material | Silk |

| Knot type | Asymmetrical (Persian) |

| Knot density | 5300 Knots per sq. dm (340 per sq. in) |

The Ardabil carpet is one of the largest Islamic carpets in existence. It is also of great historical importance. It was commissioned as one of a pair by the ruler of Iran, Shah Tahmasp, for the shrine of his ancestor, Shaykh Safi al-Din, in the town of Ardabil in north-west Iran.

In a small panel at one end, the date of completion is given as the year 946 in the Muslim calendar, equivalent to 1539-40. The text includes the name of the man in charge of its production, Maqsud Kashani.

The carpet is remarkable for the beauty of its design and execution. It has a white silk warp and weft and the pile is knotted in wool in ten colours. The single huge composition that covers most of its surface is clearly defined against the dark-blue ground, and the details of the ornament - the complex blossoms and delicate tendrils - are rendered with great precision.

History

The Ardabil Carpet is one of the world’s most celebrated carpets, woven in 1539-40 for the Safavid dynasty in Iran. It is a magnificent example of courtly design, as well as weaving technology, and has a remarkable significance for Safavid dynastic kingship. Together with its twin (today in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), the carpet was produced for the ancestral shrine of the Safavid shahs, the pious foundation built around the tomb of Shaykh Safi al-Din (d.1334), in Ardabil, northwestern Iran. At the time when these two carpets were commissioned, Safavid shah Tahmasp (r.1524-1577) was completing a significant expansion to the shrine complex, with new buildings allowing for greater emphasis on his dynasty’s right to kingship. Cementing the Safavids’ very recent conquest over Iran (led by Tahmasp’s father Isma`il), this kingship was also claimed as a moral entitlement, thanks to direct descent from their saintly ancestor, Shaykh Safi. Under Tahmasp, the Safavids further claimed their family bloodline went back to the Shi`a Imams and ultimately to the Prophet himself. This sacred lineage made the shrine of Ardabil very important as a basis of Safavid royal entitlement, which explains why Tahmasp expanded the complex with such splendour. Based in the capital of Tabriz, Safavid court culture also emphasised the dynasty’s magnificence through the visual arts, with an extraordinarily beautiful and complex design tradition produced for the arts of the book and other media. The specific design of the Ardabil Carpet therefore, in its complex design, iconography and site-specific format, confirm a Safavid message of kingly magnificence, pious charity, and divine grace.

As noted above, the Ardabil Carpet at the V&A has a twin, which is now in a museum in Los Angeles. It is important to think of the V&A’s carpet as part of a twin commission, designed for the Safavid shrine estate. Measuring approximately 10m each in length and 5m in width, the two carpets were designed to lie side by side, perfectly occupying a square space under the dome of the Jannat-sara, one of the new buildings completed by Shah Tahmasp at the shrine. This grand chamber would certainly have been used by Tahmasp in 1544 as a royal reception hall, when he invited the exiled Mughal emperor Humayun to visit the royal shrine. Both of these men loved the arts. As is well documented, Humayun was deeply taken by the court arts of Iran, and he would return to India with a number of Safavid court artists in his entourage. The impact of Humayun’s visit to Ardabil, when he walked over the twin carpets, may have contributed to that lasting impression.

Purchased in 1893 from the art-import firm Vincent J. Robinson & Co. Ltd., 34 Wigmore Street, London. Robinson's in turn had purchased the carpet from Ziegler's of Manchester, a trading firm with offices in both Tabriz and Sultanabad (modern Arak) in Iran: Ziegler's (directly or indirectly, through Tabriz-based carpet dealer Hildebrand Stevens) bought the carpet in 1888 from the shrine of Shaykh Safi in Ardabil, repairing it heavily. In 1889-90, the shrine authorities completed new restoration works on the earthquake-damaged buildings of the complex: arguably, the carpet was originally sold in order to fund this renovation. By 1892, the Ardabil Carpet was on display in Vincent Robinson's showroom.

The Museum first learned of the Ardabil Carpet from John Edward Taylor, a wealthy private collector who brought it to the Director's attention over the summer of 1892. In January 1893, the institution offered to pay £1,500 to acquire the carpet. Further funds were still needed to reach an offer acceptable to Edward Stebbing, the managing director at Vincent Robinson's, however, and so Taylor volunteered to raise the required sum through a group of private donors. By March of 1893, there were still insufficient funds, and after some consultation with two influential Art Referees William Morris Carpet and Frederic Leighton, the Museum decided to increase the initial proposed spend to £1,750 for the Ardabil Carpet. This was accepted by Stebbing and the sale went ahead, with further payments expected from Taylor (who had guaranteed £250) and others. The private donors noted in the Museum's documentation include Taylor, Morris (who offered to contribute £20), A.W. Frank, E. Steinkopff, "and other gentlemen".

At the time of its purchase by the South Kensington Museum, the Ardabil Carpet was discussed with enthusiasm as a unique object. However it was woven together with a second carpet, as a matching pair. Both were sourced from the Ardabil shrine, and in 1892 Vincent Robinson sold the twin abroad to the American tycoon Charles Tyson Yerkes for $80,000, apparently on condition that the carpet should not return to Britain. From the Yerkes collection, this second Ardabil Carpet was sold on to Joseph Raphael De Lamar, then to the art dealer Joseph Duveen, and finally in 1938 to John Paul Getty, who donated it in 1953 to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where it remains today.

In 2006, the Museum created the vast display case in the centre of the Jameel Gallery, so that the carpet can be seen as intended, on the floor. It is lit for ten minutes on the hour and half hour, in order to preserve its rich colours.

Materials

Foundation and Pile

Wool yarns worked with Sehna or Persian knots into firm and close pile on undyed silk warps and wefts hold the incredible design of the Los Angeles and London Ardabil Carpets.

Techniques and structures

Color and dyeing

The stunning filler pattern incorporates ten colours. The dyes were made from natural materials like pomegranate rind and indigo, so the shades vary slightly, producing a ‘ripple’ effect where darker and lighter batches of wool were used.

Motifs and patterns

The entire surface of the Ardabil carpet is covered by a single integrated design - an impressive feat considering the carpet's great size. The border is composed of four parallel bands. It surrounds a huge rectangular field, which has a large yellow medallion in its centre. The medallion is surrounded by a ring of pointed oval shapes, and a lamp is shown hanging from either end. This centrepiece is matched by four corner-pieces, which are quarters of a similar but simpler composition, without the lamps.

The lamps shown hanging from the centrepiece are of different sizes. Some people think this was done to create a perspective effect - if you sat near the small lamp, both would appear to be the same size. Yet there is no other evidence that this type of perspective was used in Iran in the 1530s, and the lamps themselves are shown as flat shapes rather than as three-dimensional objects. Another view is that the difference is a deliberate flaw in the design, reflecting the belief that perfection belongs to God alone.

The Ardabil Carpet has a medallion design: the main field has a bold central medallion (also called a shamsa) radiating oval pendants. Quarter versions of this medallion are repeated in the four corners of the main field. Along the central axis of the carpet, two hanging lamps are depicted: representing divine light, these lamps refer to the Safavid dynasty’s claim to direct descent from the Prophet, whose holy nature is often described in terms of light (or Nur-Muhammadi). The backdrop of the main field is an extraordinary performance of Safavid court design: there are two independent systems of spiralling leafy plant scrolls, laid one above the other, one with dark red stems, the other with thinner cream stems, all against a dark blue ground. The main border is a series of lobed cartouches, each containing designs of cloudbands and lotus flowers. Beautiful and complex design motifs such as these were also produced for manuscript illumination and bookbinding, and many other media, in the Safavid period.

Weaving techniques

Width: 530 cm non-inscription end, Width: 529.5 cm middle, Width: 535.5 cm inscription end, Length: 1032.5 cm left side looking from inscription end, Length: 1044 cm middle, Length: 1031 cm right side looking from inscription end

The exact knot-count of the Ardabil carpet varies throughout its structure, as is typical, and the given count of 340 knots per inch (equivalent to 5,472/dm2) is therefore an average value. The Los Angeles Ardabil carpet in turn has been recorded to hold an average of 350 knots per square inch: the two carpets therefore have roughly the same knot-count. This near-parity supports the accepted proposal that the two carpets were woven by the same team at the same time.

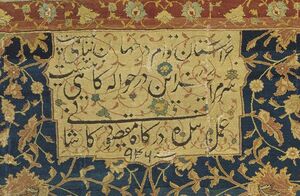

Marks and inscriptions

We can date the carpet exactly thanks to an inscription on one edge, which contains a poetic inscription, a signature - 'The work of the slave of the portal, Maqsud Kashani’, and the date, 946 in the Muslim calendar, equivalent to AD 1539 - 1540. Maqsud was probably the court official charged with producing the carpet and not a slave in the literal sense.

جز آستان توام در جهان پناهی نیست

سرمرا بجز این در حواله گاهی نیست

عمل بنده درگاه مقصود کاشانی

۹۴۶ سنه

Joz āstān-e to-am dar jahān panāh-ī nīst

Sar-e marā be-joz īn dar ḥawāla-gāh-ī nīst

ʿAmal-e banda-ye dargāh Maqṣūd Kāšānī

sana 946

Except for thy threshold, there is no refuge for me in all the world. Except for this door, there is no resting-place for my head.

The work of a servant of the court, Maqsud of Kashan.

The inscription is knotted into a white-ground panel at one end of the field. Written in nastaliq script, the first two lines are Persian verses quoting the poet Hafiz, while the third line takes the form of a signature, giving the name Maqsud Kashani ("of Kashan") and the date 946H.

Gallery

Ardabil Carpet (1539-1540), Victoria Albert Museum

Ardabil Carpet (1539-1540), Lacma Museum

See also

References

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-ardabil-carpet

- http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O54307/the-ardabil-carpet-carpet-unknown/

- http://d2aohiyo3d3idm.cloudfront.net/publications/virtuallibrary/0892360151.pdf, THE ARDABIL CARPETS, Rexford Stead